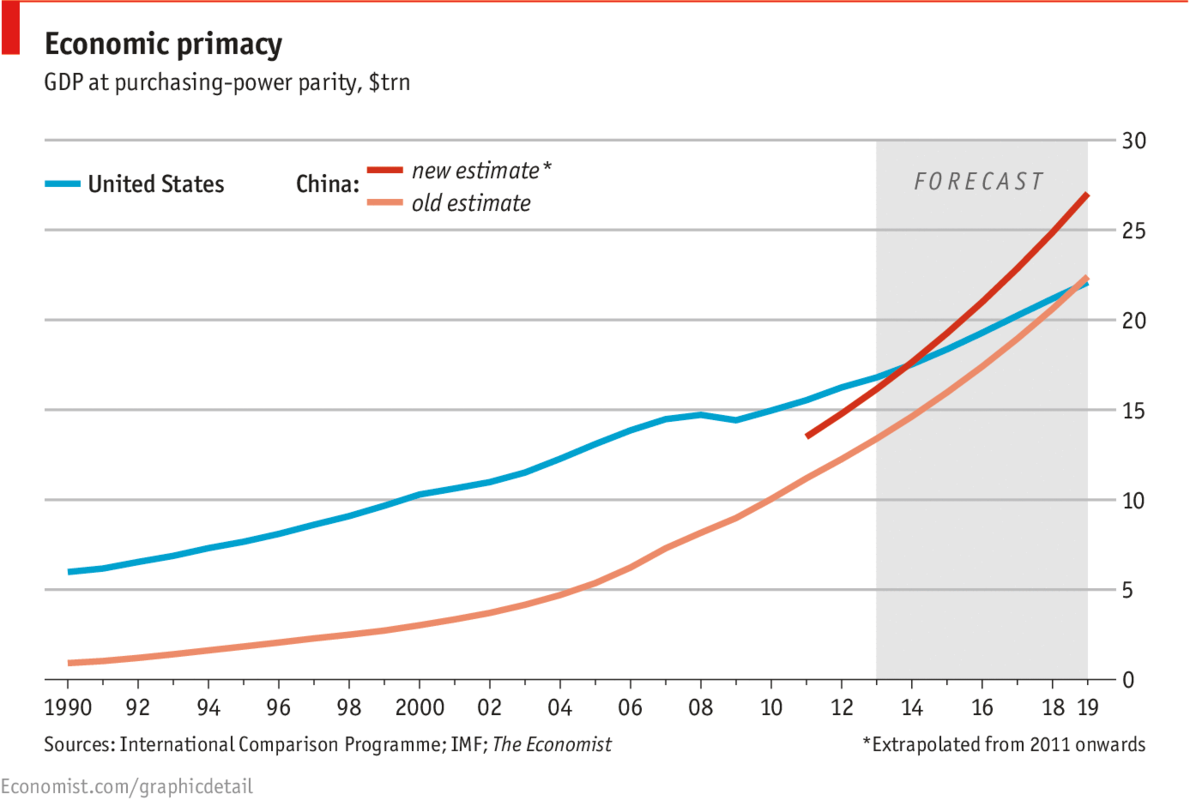

A propósito de los debates sobre el tamaño del PBI de los países más grandes del planeta, The Economist publicó una serie de notas acerca de las predicciones en el futuro más próximo, de las que se deduce que, si bien se venía previendo que la economía China podía superar a la estadounidense para 2019 (debido a que, aún estando por debajo en niveles, muestra tasas de crecimiento mucho mayores), es necesario revisar esos pronósticos ya que si sólo se utiliza un tipo de medición específica (el Purchasing-Power Parity en inglés -PPP-, la Paridad de Poder Adquisitivo en castellano) en lugar de los dólares corrientes, este evento podría ocurrir este mismo año o el próximo.

Ello se debe a cuestiones cambiarias, básicamente.

UNTIL 1890 China was the world’s largest economy, before

America surpassed it. By the end of 2014 China is on track to reclaim

its crown. Comparing economic output is tricky: exchange rates get in

the way. Simply converting GDP from renminbi to dollars at market rates

may not reflect the true cost of living. Bread and beer may be cheaper

in one country than another, for example. To account for these

differences, economists make adjustments based on a comparable basket of

goods and services across the globe, so-called purchasing-power parity

(PPP). New

released on April 30th from the International Comparison Programme, a

part of the UN, calculated the cost of living in 199 countries in 2011.

On this basis, China’s PPP exchange rate is now higher than economists

had previously estimated using data from the previous survey in 2005: a

whopping 20% higher. So China, which had been forecast to overtake

America in 2019 by the IMF, will be crowned the world's pre-eminent

country by the end of this year according to

calculations. The American Century ends, and the Pacific Century begins.

THERE are a number of ways to measure the might of a nation: military

power, commercial clout, cultural influence. But ever since

statisticians started rigorously calculating economic output in the

1930s, economists have fixated on one measure: gross domestic product

(GDP). By one variant of that yardstick, China is on the verge of

becoming the world’s mightiest country.

Our interactive prediction tool lets you estimate when China’s GDP might eclipse America’s at market exchange-rates

Comparing the economic output of countries is tricky. The most

straightforward way is to convert GDPs into a single currency (usually

dollars) at market exchange rates. This is a good way to gauge

countries’ international heft, and by this measure China’s economy is

still 43% smaller than America’s. But for comparing living standards or

growth rates, market exchange rates can be misleading. Exchange rates

can be volatile, yielding vastly different GDP values on different days.

Governments often meddle with them. Most important, they are influenced

by prices for internationally traded items, but they do not reflect the

cost of purely domestic goods and services, such as haircuts or bus

rides. Since rich-world barbers are more expensive than those in poor

economies but not vastly more productive, using market exchange rates to

compare GDPs understates the productive capacity and living standards

of the emerging world.

The International Comparison Programme (ICP) was established in 1968

in an attempt to allow for such things. Statisticians collate the cost

of comparable goods and services in different countries. They then

adjust output figures to take account of the lower cost of those items

in poorer countries—a method known as purchasing-power parity (PPP).

The Economist’s

Big Mac index is based on the same premise, although it looks at the

price of just one item. The ICP’s first survey in 1970 took in only ten

countries. The latest, released on April 30th but based on prices from

2011, provides data for 199 economies and estimates for another 15 (see

chart).

The previous ICP survey, released in 2005, attracted criticism for

its results from China, which were based on data from just 11 cities.

This, some argued, overestimated the cost of living and therefore

underestimated the size of the Chinese economy on a PPP basis. That,

along with the difficulty of accounting for varying rates of inflation

since 2005, meant the PPP data were getting ever more inaccurate: the

new data put China’s PPP exchange rate 20% higher. The old PPP exchange

rates had suggested that China’s economy would overtake America’s in

2019; the new ones imply that it will do so by the end of this year.

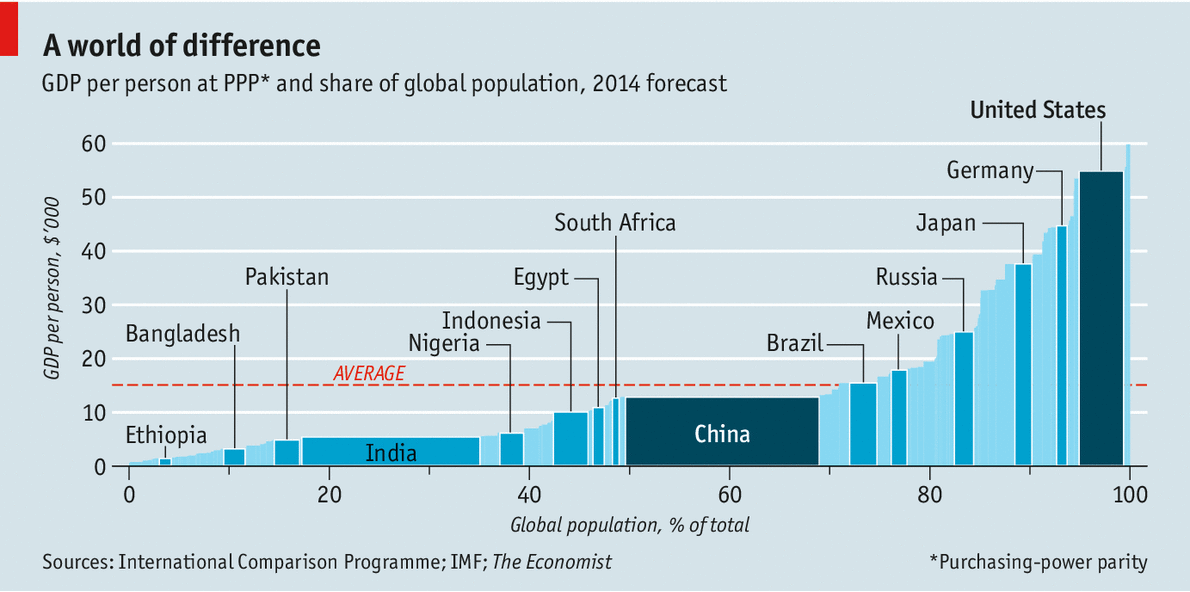

A similar uprating has caused a shuffling of the pack elsewhere, too.

Indonesia, which was thought to be the world’s 15th-biggest economy, is

now ninth. Indeed the six biggest emerging economies now produce goods

and services of equal value to the six biggest rich countries. Further

number-crunching is required to work out the impact of the new exchange

rates on the global poverty rate (which is typically defined to include

all who live on less than $1.25 a day at PPP); that will take a year or

more. But the ICP’s report does tentatively suggest that “the world has

become more equal”, as the number of people living in countries with a

GDP per person of at least half of America’s has risen slightly, from

15% in 2005 to 16% in 2011.